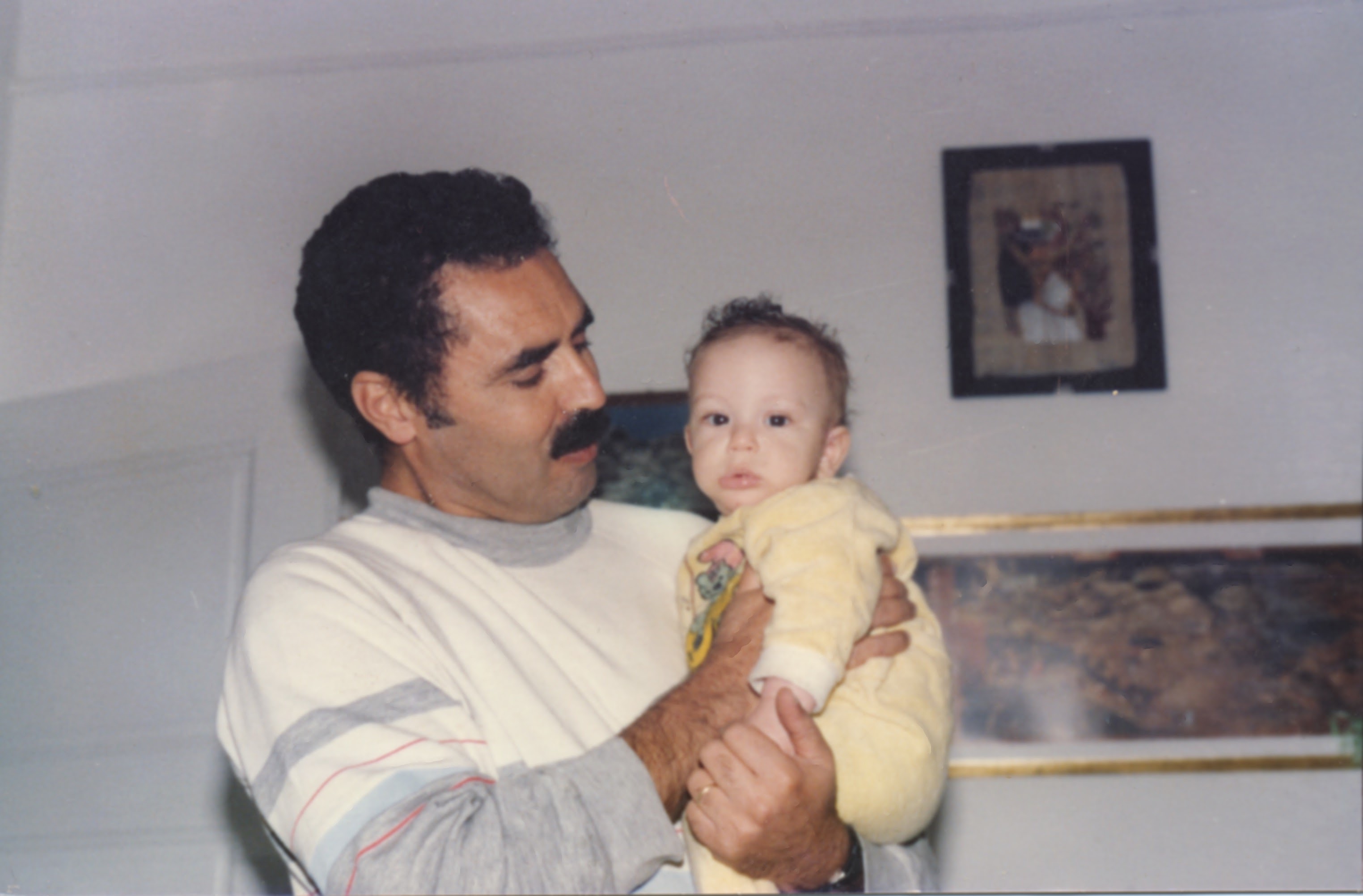

My Father Died

He was a workaholic with a government job in a third-world country. It’s useless when you think about it: it doesn’t earn you much money or recognition, not even a great deal of respect—except from your peers, and there aren’t many of them when you’re a sociology professor in, again, a third-world country. What it gets you, for sure, is less time with your family.

Still, he was my personal hero.

He believed people didn’t need much to survive. He took special care to eat healthy, avoided any kind of drug (coffee included), exercised, and most importantly, he made me feel special. I always knew deep in my heart that whatever problem I faced, he would go out of his way to help.

He was an avid reader and always had a book within arm’s reach. I can still remember how he used to take naps on Sundays with the book he’d been reading resting over his eyes to block out the light, and me having to wake him up for some reason.

We didn’t do much together, except for hiking trips and, after he and my mom divorced, the occasional restaurant. I was mostly into my own stuff (video games), which he didn’t approve of. That’s when our disagreements about life choices started. He believed I wasn’t doing my best, that I was wasting my time, that I should focus more on my studies.

Then, on a Monday afternoon, he died.

I wasn’t in a good place back then—long before this happened. I had made a bad choice and I was struggling to keep up with it. After my baccalaureate, I’d chosen poorly and ended up somewhere I didn’t like: a preparatory school. One of the best in the country—and for the whole first year, I hated every second of it. I hated it so much that I stopped going altogether and ended up falling behind, among the lowest 1%.

I was used to being an A-student, and most of my life I didn’t have to work for it. I was always busy hanging out with my boys, stealing the neighbor’s grapes, chilling in the nearby semi-forest, trying to build stuff, or doing whatever boys do in a rough neighborhood with an electronics dumpster nearby. At the same time, I was first in my class, my school, and even my state on some occasions. So I wasn’t accustomed to failure.

And I was failing—failing extremely hard.

At that point in time, I don’t remember thinking much about my future or having any kind of life plan. I mostly feared my dad’s reaction. He would be so disappointed in me if I failed a year, it would kill him.

The day he received my result sheet, I was mortified. I tried to explain the reasons behind my failure, but I can see now why he dismissed them. It was mostly excuses—without any self-evaluation or solutions. And that was normal: I was in uncharted territory, I was stuck, and I needed help.

He thought I should snap out of it, that I was completely able to turn it around, and that I should trust myself. But I was panicking, and I couldn’t help thinking he was full of it when he said, “I’m not paying for a tutor.” He was always against it; to him, it was cheating somehow.

I remember us having a huge fight: me, on the verge of catastrophe, asking him to fund the only solution I thought fit—and him turning me down. I was so pissed that night that I left his house and spent the night on the street, took the first cab home, and never spoke to him again.

A few days later, with my back against the wall, I decided I was going to snap out of it. I had my plan: I would work hard for every test as if my life depended on it. I caught up with every lesson I’d skipped—and there were a bunch of them. Preparatory school is no joke, and absorbing the first year’s lessons in four months is a huge challenge. But I decided it was my only play, and I went for it with all I had.

I kept skipping courses; instead, I was spending all my days at the library, catching up. There were some bumps at the beginning of the road, but I was turning it around and I started getting good enough grades.

He was right after all, and I was too proud to admit it. So I kept ghosting his calls. I saw him once at my granddad’s funeral on my mother’s side. He was wearing his olive green coat. We didn’t talk much. I wasn’t close to my granddad, so I wasn’t really sad that day. It was my first funeral, and I found myself watching the ritual.

And the ghosting continued.

I was in class taking a test when the dean showed up and asked me to come to his office. I explained that I was having a test—that like every test I got, there was no chance in hell I was going to fail it—and that I’d swing by later. But he insisted. The teacher agreed to let me continue later, and so I went.

One of the perks of being a lousy student is that you build some kind of relationship with your school’s administration. I was no stranger to the dean’s office. We’d had many heated discussions in there—mostly him trying to scare me into being a better student, or guilting me into it. Doing his job, I guess. At some point, I remember him trying the line, “You should study for your country!” It seemed so far-fetched I brushed it away with a laugh.

That day, the dean didn’t have the same judgmental look he used to give me. Instead, he put a hand on my shoulder and stayed silent.

We walked.

When we finally got to his office, a high-ranking government officer (and a relative) was there. My mind started racing, thinking of all the reasons he could be there—and all the ways he could help me pass the year. He calmly explained that my dad was very sick, that he’d been hospitalized, and that he really needed to see me, and that he would drive me there himself.

This felt very unlikely because my dad was the healthiest person I knew. Okay, he was sixty years old. But compared to men twenty years younger than him, he seemed in good shape. He had recently biked 60 kilometers in 3 hours on a city bike. He was always finding ways to exercise: starting obscure reconstruction projects at home, moving dirt from place to place by himself instead of paying someone like everyone does, and hiking regularly up a mountain to tend to his olive trees. A year before, he swam what I guessed was 2 kilometers when I teased him about the small belly he had started developing.

So I wanted to know what he had, how he ended up in a hospital, and why he didn’t even try to call me himself. But there was no answer. I kept getting: “He is very sick. You need to come with me now.”

So I went.

The inside of the car was dark. It had some fancy cloth over the windows. My little brother was already in the back seat. He didn’t look well. I kept asking my questions, and my brother shouted that our dad was dead. I don’t remember if I cried then. I had trouble wrapping my head around the idea, so I just stayed silent, staring bleakly at the dashboard.

It took us an hour to get there. I noticed we didn’t stop by the hospital where he would’ve been lying if he were really hospitalized. Then we were there, at my uncle’s house. Lots of chairs were lined on both sides of the street. A huge crowd was gathered inside and outside. The moment I got out of the car, it hit me.

My father was dead.

I remembered our last fight. His disappointment. My ghosting. And I started sobbing frenetically. I remember someone embracing me. I was there for some time. I saw the body. Someone asked me to kiss his forehead. His eyes were closed. I could glimpse his teeth. I remember how cold his forehead felt on my lips, and I instantly regretted kissing it. It felt so wrong.

Then it all went dark.

Not that I fainted or anything. It’s just that our minds tend to block some memories. Self-preservation, I guess. I completely forgot everything that happened in the next couple of days. I’ve been told there were lots of tears on my part, a funeral, and condolences. Lots of people showed up, and they all lined up to kiss me on both cheeks while I was sobbing.

My first memory afterward was staring out the window of a car. One of my dad’s best friends was driving me home, and we were passing by a high school around 10 a.m. Students were having their break—sitting on benches, laughing, doing whatever fifteen-year-olds do. I remember wondering how they could be fine on such a day. My world was crushed, and I had completely forgotten it was just a normal day for everyone else.

At that point, I was in over my head. I completely shut down, gave up on succeeding that year, and felt kind of relieved that my dad wasn’t there to see me fail. In a very twisted way, my problem was solved. And I just stayed home, in my room, for weeks.

The summer that followed was difficult. It turns out all hell breaks loose when the only provider in a family dies. My parents being divorced didn’t make the procedures easier. We were at a very low point, both emotionally and financially.

Luckily, my mother stepped up and took care of things. I remember finding out later, during my cousin’s wedding, that my mom didn’t have her golden rings anymore. She had this plastic, gold-looking ring instead. And I understood where she got the money to keep us afloat that summer. A few months later, we started getting my dad’s insurance money. It wasn’t much, but it was enough.

By the end of summer, I wasn’t myself anymore. Failing my school year made me lose all my self-esteem. Sorrow made me feel numb and indifferent. Nothing could get to me anymore. There was a dark cloud hanging over the future of what was left of my family, though. The insurance money had an expiration date. I had four and a half years to earn a decent living.

I needed a plan.

It was time to get back to reality…